18 Aug 2014

Scientists are trained to observe and read with critical eyes and write with technical language. Primary research articles are dense and require both experience and significant background knowledge to decipher. Translating primary research for non-experts can be difficult because many concepts have no generalizable equivalent. A handful of scientists have had a knack for effective translation - Richard Feynman, Carl Sagan, Neil deGrasse Tyson, for example - but in general it seems to be an uncultivated skill.

I think that as the pace of scientific and technological progress hastens it will become increasingly important for scientists to communicate their research to both technical and general audiences. One of the reasons I was drawn to this cruise was the focus on outreach. Students and educators are brought on the cruise not only to experience science at sea but to share that experience with their communities.

John Wonderly from Leg 1 is a school teacher in Clallam Bay and Julie Nelson is a chemistry professor at Grays Harbor College. They both serve communities that have fallen on hard times where education is a critical component of economic recovery. I’ve kept in touch with John since Leg 1 and we’re developing a series of talks with UW and Clallam Bay students. I think we’ll have a lot to learn from each other.

16 Aug 2014

It is easy to think of science as a solitary effort but the truth is that collaboration is often necessary at multiple levels. Oceanographic research in particular requires the use of data collected by experts in different fields and analysis from multiple perspectives. Subsequent critical review by peers is an essential part of the process. Article manuscripts submitted to journals are also reviewed by peers selected by the journal and accepted or rejected, in theory, based on fit and scientific merit.

Collaboration is a hard skill to develop though. People (including me) tend to be protective of their creations and resistant to any perceived meddling. But creative projects benefit from criticism and iterative revision and working in a vacuum can be dangerous. At the start of Leg 1 I was fairly protective of my projects. I don't think I'd be wrong to say the entire group was. After the first few days of adjustment we became more comfortable sharing and accepting criticism. Looking back now I know that shift to collaboration was an important part of our development as students. There are less students on this leg and less overlap on projects, but I hope we can get to the same sort of collaborative spirit.

14 Aug 2014

I had a close encounter of the bird kind last night. A small seabird, likely a storm petrel, flew into the main lab around 2200. It seemed dazed and confused, possibly sick, but not visibly injured. It seemed intent on stumbling into the dark corners of the lab, so I set up a small box for it to rest (or die) in. Fortunately one of able seamen (AB - a member of the crew deck department), Dana Africa, caught wind of the wayward petrel and knew what to do. She claimed the bird was fine, if not a little frazzled, and would recover at dawn. Eight hours later she took the petrel onto the sunlit bow and the bird took off with no more trouble than it might have from a late night hangover. There's a lot of depth wrapped up in that petrel's adventure. It's sobering how much good-intentioned humans can disturb the very environment they seek to understand. It's also disturbing how poorly adapted we are for life at sea, steaming around in loud, bright, obnoxious metal machines. We're careful about our impact but we trade life for knowledge with every expedition.

13 Aug 2014

I'm a surprise addition to Leg 3. Deb Kelley called me last week and told me there was an empty bunk on the Thompson with my name on it. And when Deb Kelley calls you and tells you there's an empty bunk on the Thompson with your name on it you say "I'll start packing". So I did. Things feel familiar back on the ship. About half of the crew and science team have changed over but the "lifers" - who will stay aboard for the entire duration of the cruise - give me a sense of continuity. The student group is smaller this time around, but just as eager. I look forward to working with them.

21 July 2014

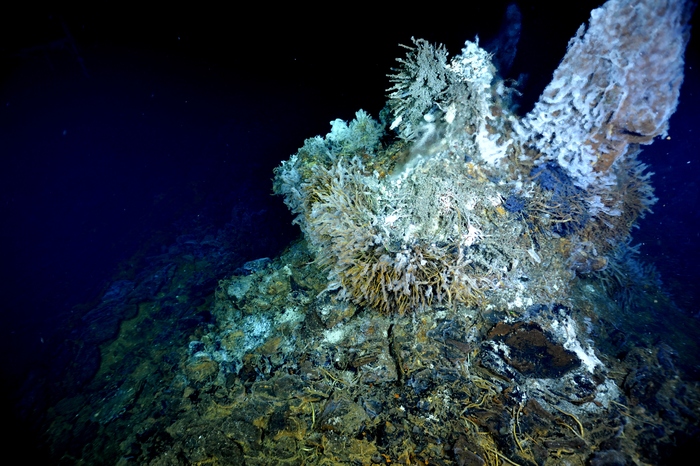

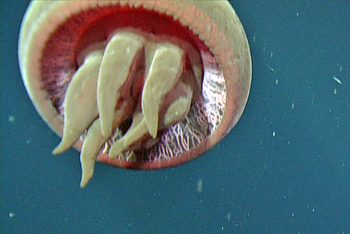

I'm writing this from inside the ROPOS control room as we leave the International District hydrothermal vent field in the caldera of Axial Seamount. Deb Kelley just led an incredible survey of two hydrothermal vents, El Gordo and Escargot. Both were covered in filamentous (stringy), white bacteria and strikingly blue ciliates (single-celled protists). I talked about the ocean blues we couldn't capture in my last update, but I'll let these pictures speak for themselves.

19 July 2014

People warned me the ocean would be blue but I didn’t really believe them. That sounds trite, but the blue is startling. No painting, photograph, or digital display does justice to the ocean’s blue.

I think part of the problem is physical. The color of large bodies of water is a result of several different physical phenomena. Other materials owe their color to less complex or even singular processes.

Visible light is a small portion of the electromagnetic radiation spectrum with wavelengths of approximately 400 to 700 nanometers. Different materials absorb or reflect light differently based on chemical composition and surface geometry. Smooth metals reflect light in a coherent direction, rough rocks reflect light diffusely at multiple different angles, and translucent materials like water absorb parts of the visible spectrum.

Most light absorption or scattering is due to electron-photon interactions. Photons of light are absorbed by individual electrons or electron-electron bonds. In water the bonds between oxygen and hydrogen absorb photons of infrared light which has no effect on visible color. However the oxygen-hydrogen bonds have a harmonic vibration which absorbs a frequency of red light and is responsible for the fundamental blue of large bodies of pure water.

Seawater is not pure, however, and particles suspended within the ocean also scatter and absorb light. The ocean surface can also partially reflect the sky's blue, but the ocean still has its hue on overcast days. I don't know enough about the physics of water/light interactions to say for certain, but I think the ocean's color is primarily due to the harmonic absorption and unique to water.

In the end I'm not entirely sure why I can't share the ocean's color. I'm not even sure if it will be physically possible to represent in another medium. If you want to truly see the sea then you'll have to come out here.

14 July 2014

The sea is black and seething

and Thompson’s drunken weaving

has all my cruise mates heaving.

No more need be said.

13 July 2014

The Thompson has a memorable smell - fresh paint, old air, fire retardant insulation, and electrical ozone. The aircraft carriers and icebreakers I’ve visited smell the same, cramped and chemical. It’s a constant reminder that I’m out of my element. That I’m just a human in a big metal boat floating through unfamiliar territory. Sometimes it gets so strong I swear I can taste it.

The smell can’t compete with the galley though – barbecue and crab cakes are on the menu tonight– and meals are a brief but welcome break.

After dinner I went out to the deck where the air was fast and fresh. We were steaming through the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Lightning streaked far to port in a storm over my side of the strait in the Olympic Mountains. Low clouds on the horizon obscured the open Pacific and our destination beyond. Back in the ship the smell wasn’t so oppressive. As I finish writing this first entry it’s starting to feel almost comfortable. Almost like home.